Fall Quarter 2024

Instructors: Nidia Bautista, Gus Wendel

Sound Methods Instructor: Doğa Tekin

Exhibition Designer: Xen Pei Hoi

Guest speakers: Melissa Acedera, Polo’s Pantry, The Creating Justice LA Peace and Healing Center Nayantara Banerjee, The Garment Worker Center Caroline Luce, UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Grant Sunoo, Little Tokyo Services Center Saba Waheed, UCLA Labor Center

Students: UHI 2024-25 Cohort.

What does it mean to listen with Downtown? How are commons experienced and interpreted in Downtown? For whom is this a sanctuary and who is at risk? Who controls this space, and how is the “right to the city” sounded? What are the sonic conditions that enable or restrict different engagements with and mobilities within DTLA?

These questions serve as a foundation for our urban humanist inquiry into the spaces of Downtown Los Angeles. Part discussion seminar, part methods workshop, the UHI fall course explored key concepts–borders and commons, spatial justice and the “right to the city”, performativity and the public sphere–that have shaped urban humanities thinking while applying those concepts to a project using the method of sound scavenging and sonic production. In particular, students investigated the theoretical and practical dimensions of the concept of the commons in the context of Downtown Los Angeles, and developed ‘sonic thick maps’ to tell a story of a place using aural layering.

Working in teams across five ‘districts’–Little Tokyo, Broadway Theater/Commercial District, Skid Row/Arts District, Bunker Hill, and the Garment/Flower District–students approached their sonic investigations in diverse ways, ranging from conducting and recording conversations with local residents and activists, to remixing sonic traces and fragments, and integrating their own voices and reflections into the recording and production process. Each team also made accompanying zines to contextualize their sonic maps and contain their material and sonic archives.

The maps collectively reveal how the spaces that delineate the commons are fundamentally social constructs, by which inside and out, safe and perilous, ours and not-yours, welcome and hostile, are defined in social, cultural, political terms, and upheld through spatial disciplines like planning and architecture. Yet, the maps also illustrate the constant contestation and renegotiation of these spaces by those who inhabit them. Guided by Sara Ahmed’s notion of dis/orientation,1 students engaged with these tensions by critically centering embodiment as the medium through which they accessed these spaces. These sonic thick maps invite us to think about how we direct and redirect our attention toward different objects, lived experiences, histories, and the repeated behaviors and actions that shape Downtown LA.

The task engenders another set of inquiries, namely, how to sonically engage with space while foregrounding issues of positionality and ethics. In class, discussions centered on implications of engaging with Downtown from a position of privilege and within the context of the neoliberal university. In contrast to the heavy-handed and historically top down approaches of planning and architecture, listening–as Pauline Oliveros suggests– offers an alternative form of engagement. Through quantum listening, which entails “listening in as many ways as possible simultaneously—changing and being changed by the listening”,2 students explored how sound can disrupt binary thinking, invite reciprocity, and foster mutual transformation. Their productions include layers of recordings, manipulated in relation to each other through spatial considerations such as directionality, distance, and movement, temporal considerations such as speed, rhythm, and past/present/futures, and narrative considerations such as perspective, metaphors, and storylines. With these methods, each map performs a unique aural argument grounded in its respective place in Downtown LA.

The exhibition of these sonic maps, aptly titled Tuning the Commons, reveals the fluid and contested nature of urban spaces. Sound, as an embodied and spatial medium, indexes how we become differently oriented and attuned, affirming that to be urban humanists means “to always be a body within a sonic environment”.3 It amplifies the layered histories of cultural emplacement, political contestation, social upheaval, and struggles over spatial control and resistance giving shape to Downtown LA. Taking seriously Soja’s articulation of ‘space’ as infinitely complex, as simultaneously individual, collective, temporal and social,4 the practice of listening becomes an essential means to engage with space, and a starting point for considering what ‘spatial justice’ might look and sound like in Downtown LA. The exhibition challenges us to listen deeply and engage meaningfully, blurring simplistic divisions of insider/outsider while opening new possibilities for how we position ourselves and each other in space.

Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Duke University Press, 2006).

Pauline Oliveros, Quantum Listening (Silver Press Company, 2024), p. 30.

Jacqueline Jean Barrios and Kenny H. Wong, ‘City Analog: Scavenging Sonic Archives and Urban Pedagogy’, Review of Communication, 20.4 (2020), pp. 367–87 (p. 368)

Edward W. Soja, Seeking Spatial Justice (U of Minnesota Press, 2010).

The Sound of Culture: Sonic Control and its Subversion in Bunker Hill

Students: Ames Cassell Loji, Sydney Patterson, Xujun Xu

Bunker Hill is old town, lost town, shabby town, crook town.

—Raymond Chandler, The High Window

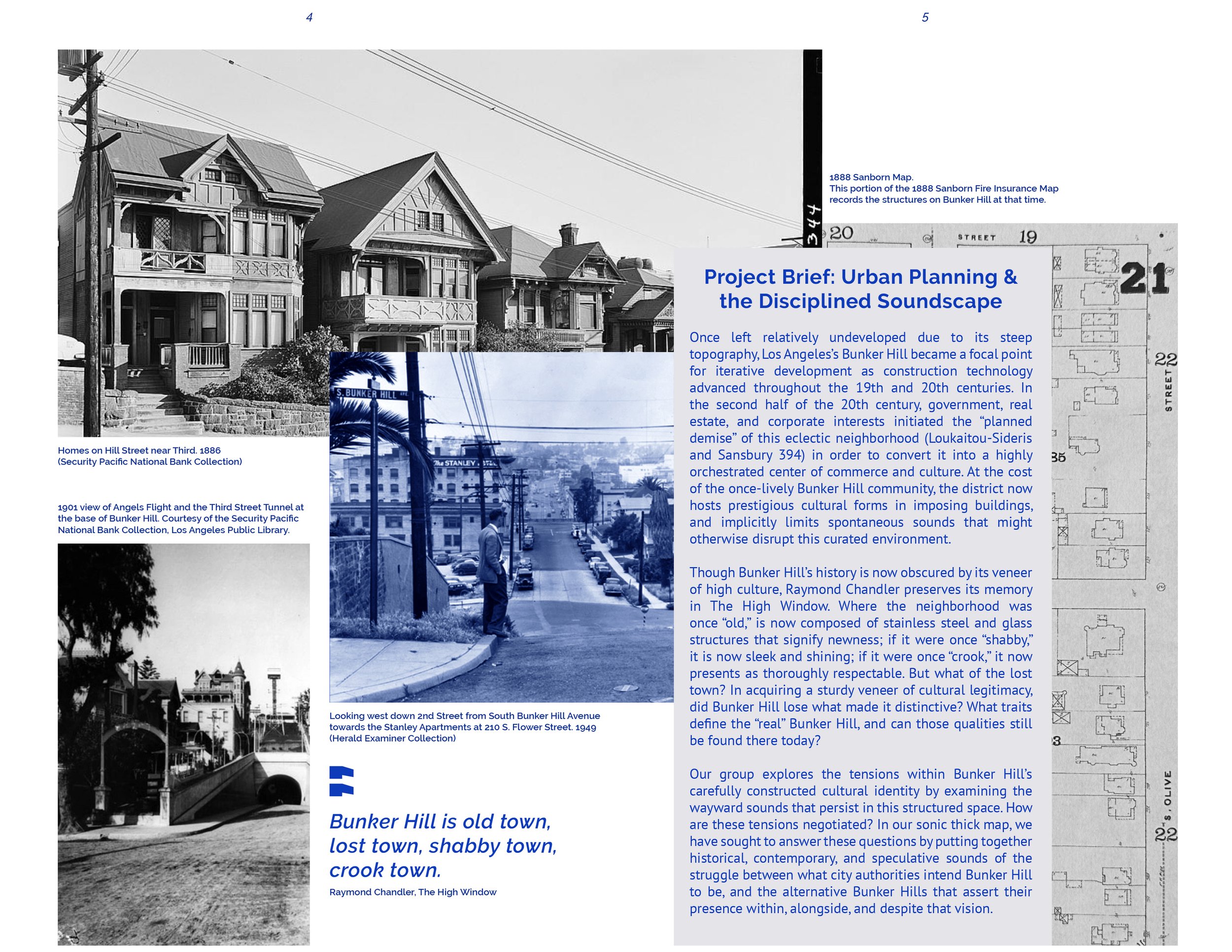

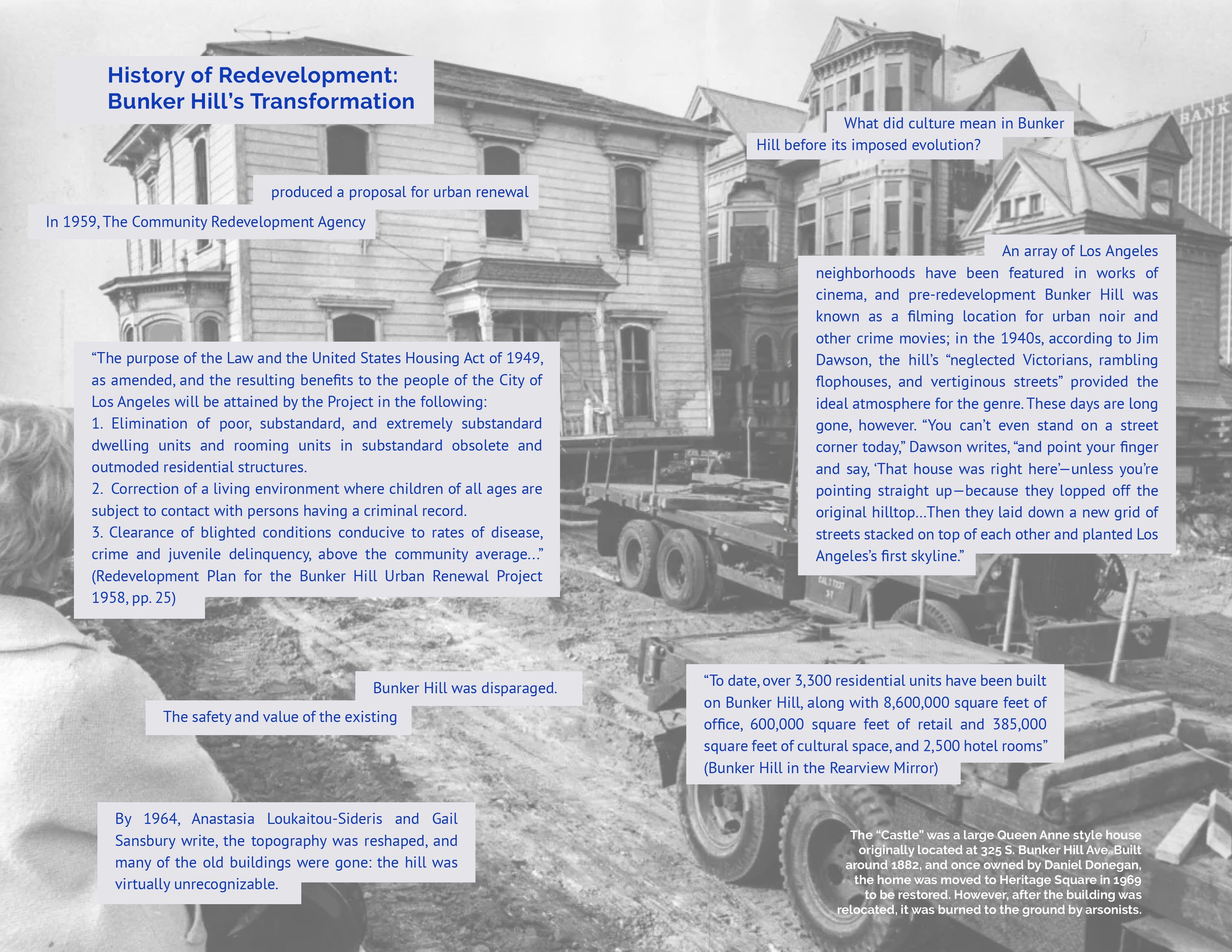

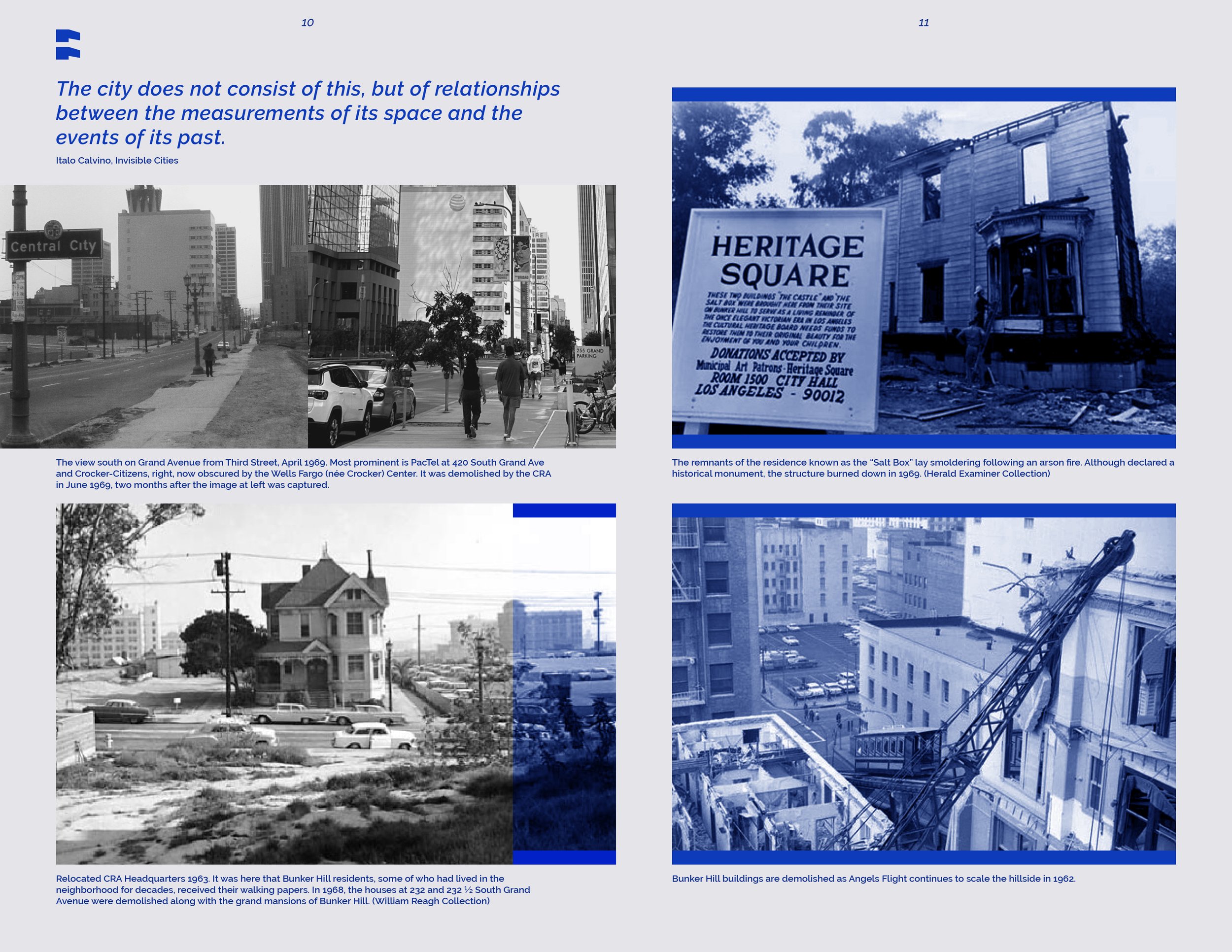

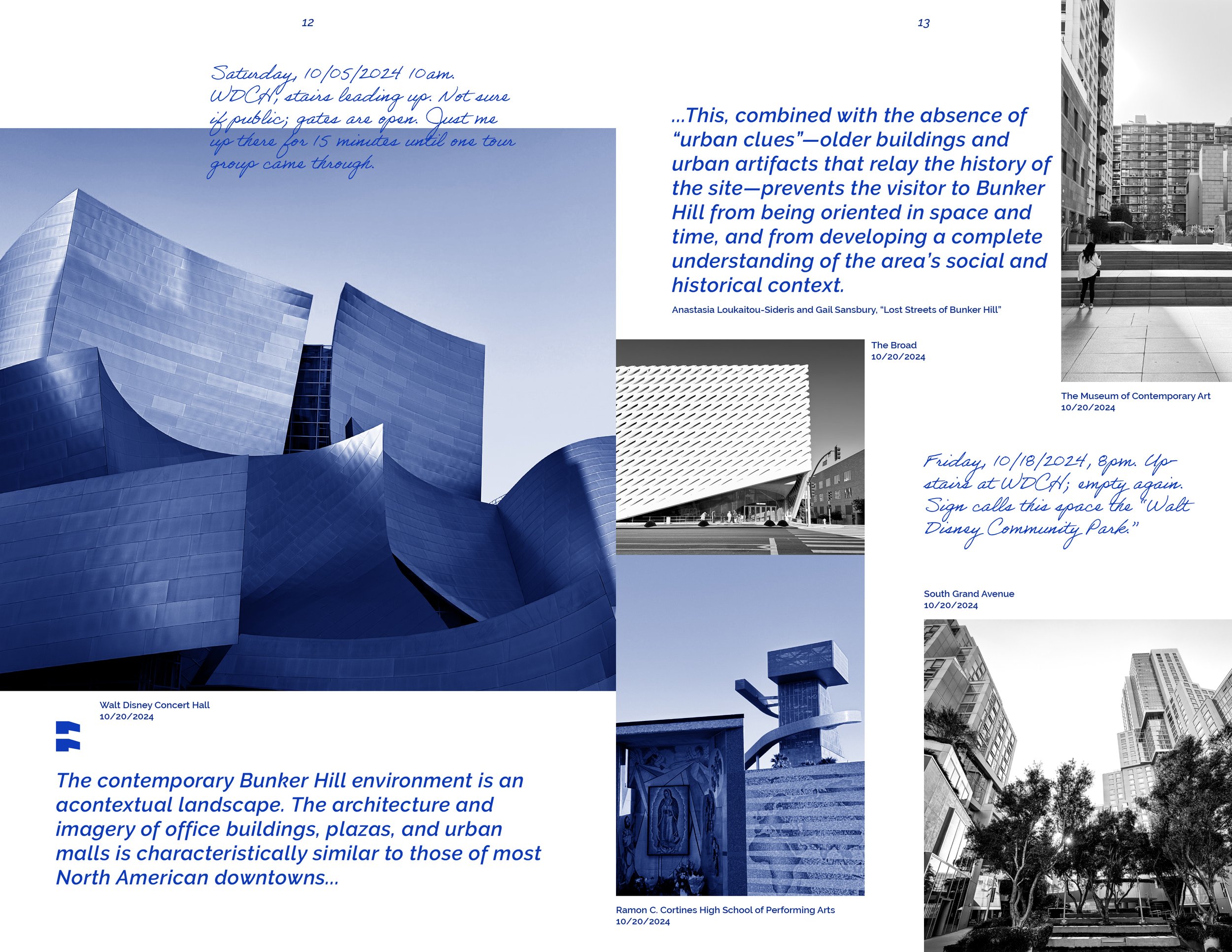

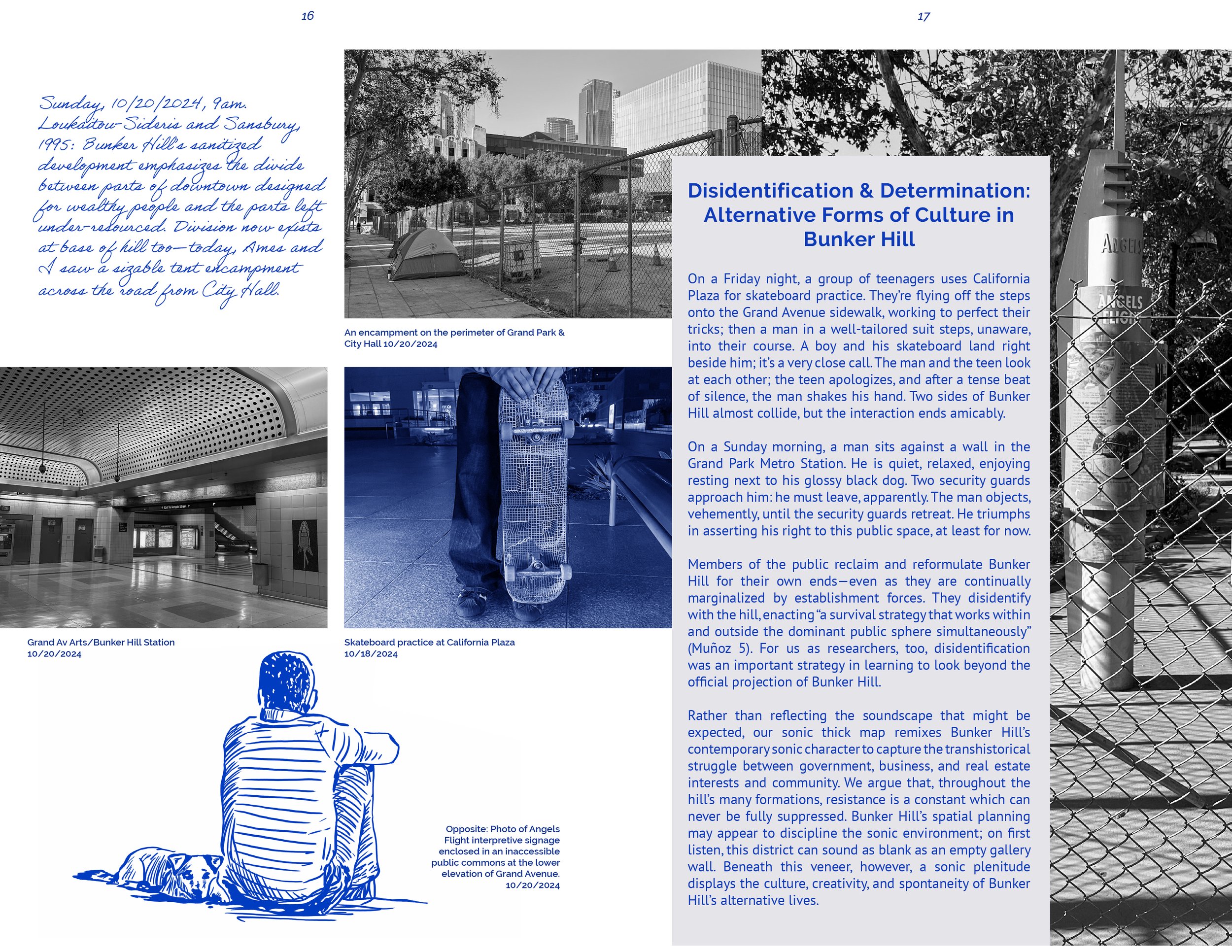

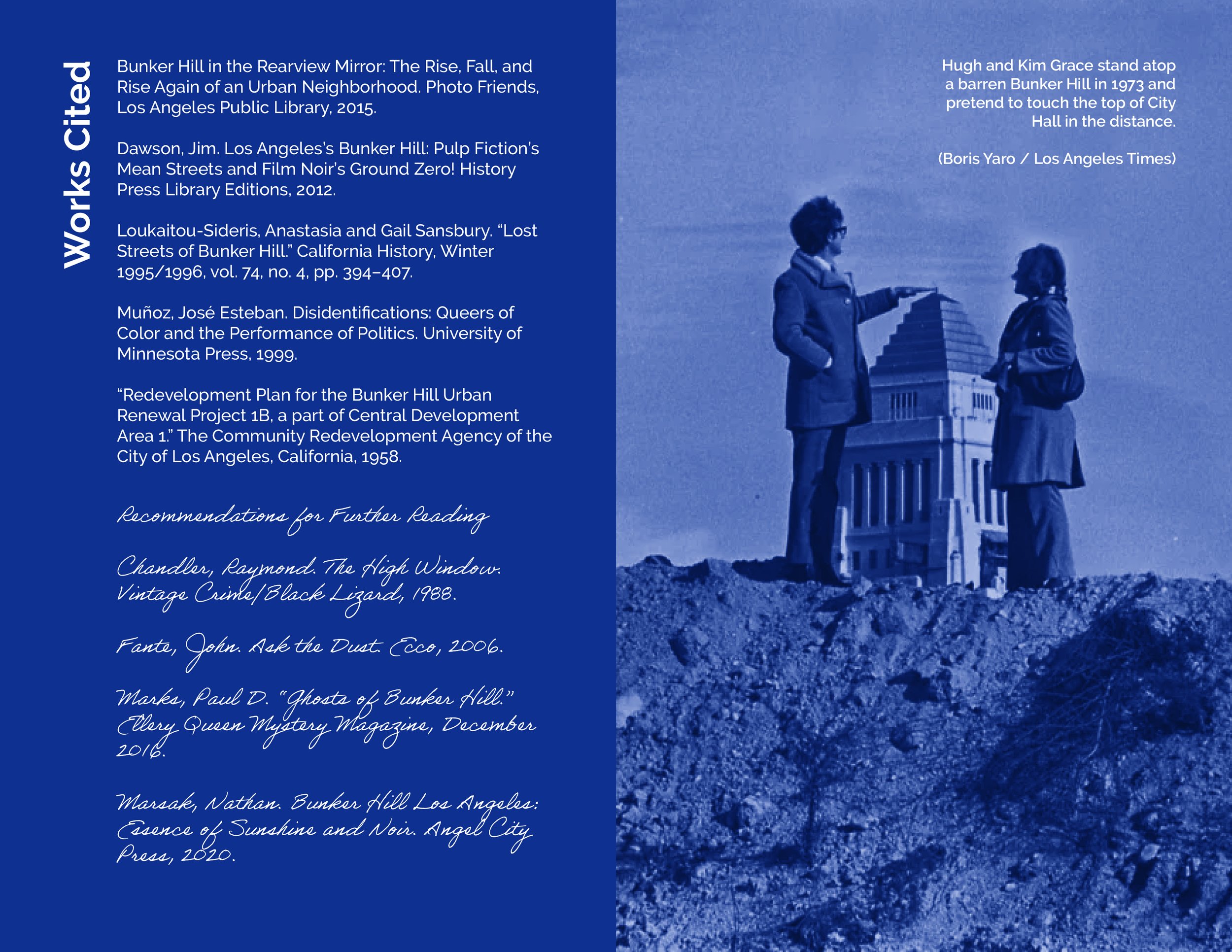

Once left relatively undeveloped due to its steep topography, Los Angeles’s Bunker Hill became a focal point for iterative development as construction technology advanced throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. In the second half of the 20th century, government, real estate, and corporate interests initiated the “planned demise” of this eclectic neighborhood (Loukaitou-Sideris and Sansbury 394) in order to convert it into a highly orchestrated center of commerce and culture. At the cost of the once-lively Bunker Hill community, the district now hosts prestigious cultural forms in imposing buildings and implicitly limits spontaneous sounds that might otherwise disrupt this curated environment.

Though Bunker Hill’s history is now obscured by its veneer of high culture, Raymond Chandler preserves its memory in The High Window. The neighborhood that was once “old” is now composed of stainless steel and glass structures that signify newness; if it were once “shabby,” it is now sleek and shining; if it were once “crook,” it now presents as thoroughly respectable. But what of the lost town? In acquiring a sturdy veneer of cultural legitimacy, did Bunker Hill lose what made it distinctive? What traits define the “real” Bunker Hill, and can those qualities still be found there today?

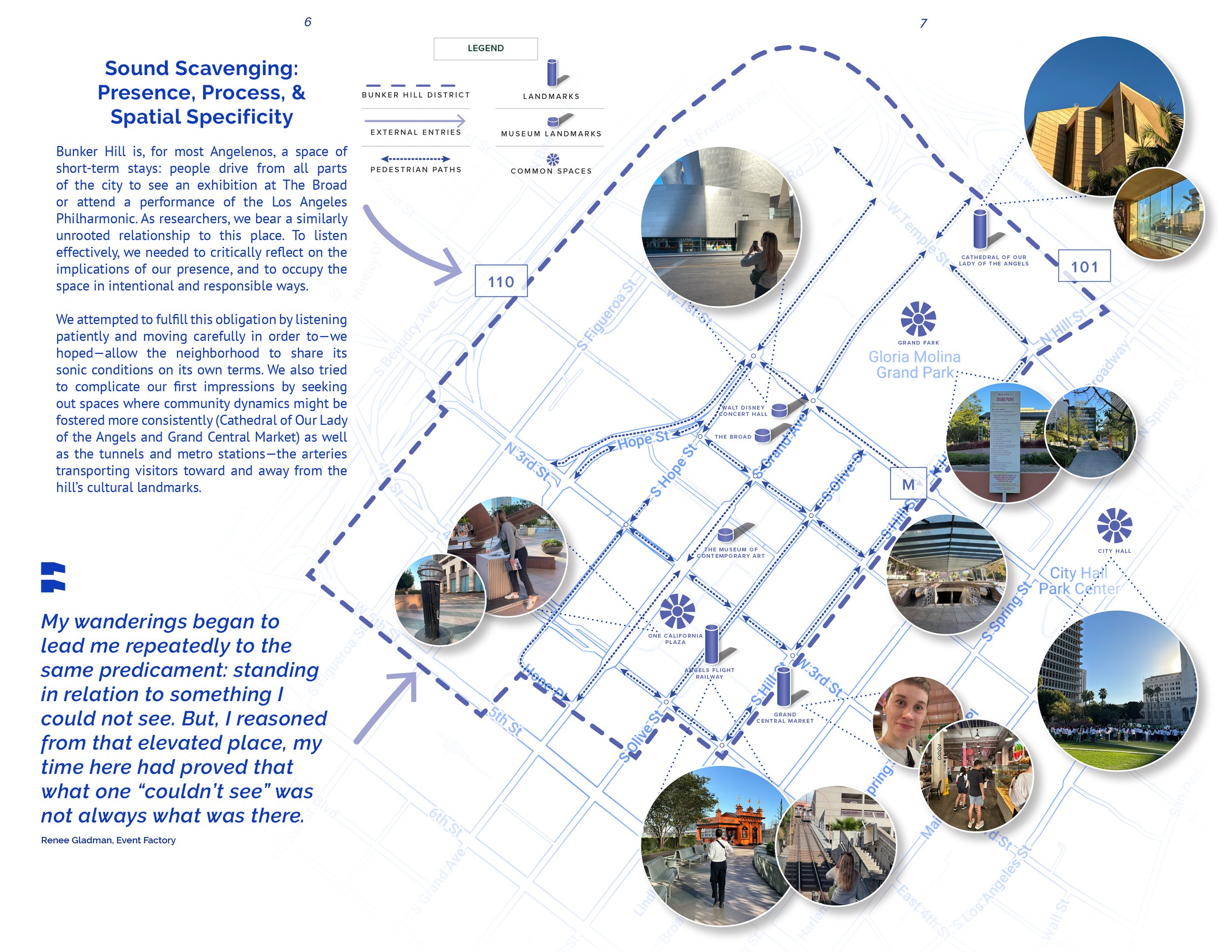

Our group explores the tensions within Bunker Hill’s carefully constructed cultural identity by examining the wayward sounds that persist in this structured space. How are these tensions negotiated? In our sonic thick map, we have sought to answer these questions by putting together historical, contemporary, and speculative sounds of the struggle between what city authorities intend Bunker Hill to be, and the alternative Bunker Hills that assert their presence within, alongside, and despite that vision.

Rather than reflecting the soundscape that might be expected, our sonic thick map remixes Bunker Hill’s contemporary sonic character to capture the transhistorical struggle between government, business, and real estate interests and community. We argue that, throughout the hill’s many formations, the sound of resistance is a constant which can never be fully suppressed. Bunker Hill’s spatial planning may appear to discipline the sonic environment; on first listen, this district can sound as blank as an empty gallery wall. Beneath this facade, however, a sense of sonic plenitude attests to the culture, creativity, and spontaneity of Bunker Hill’s alternate lives.

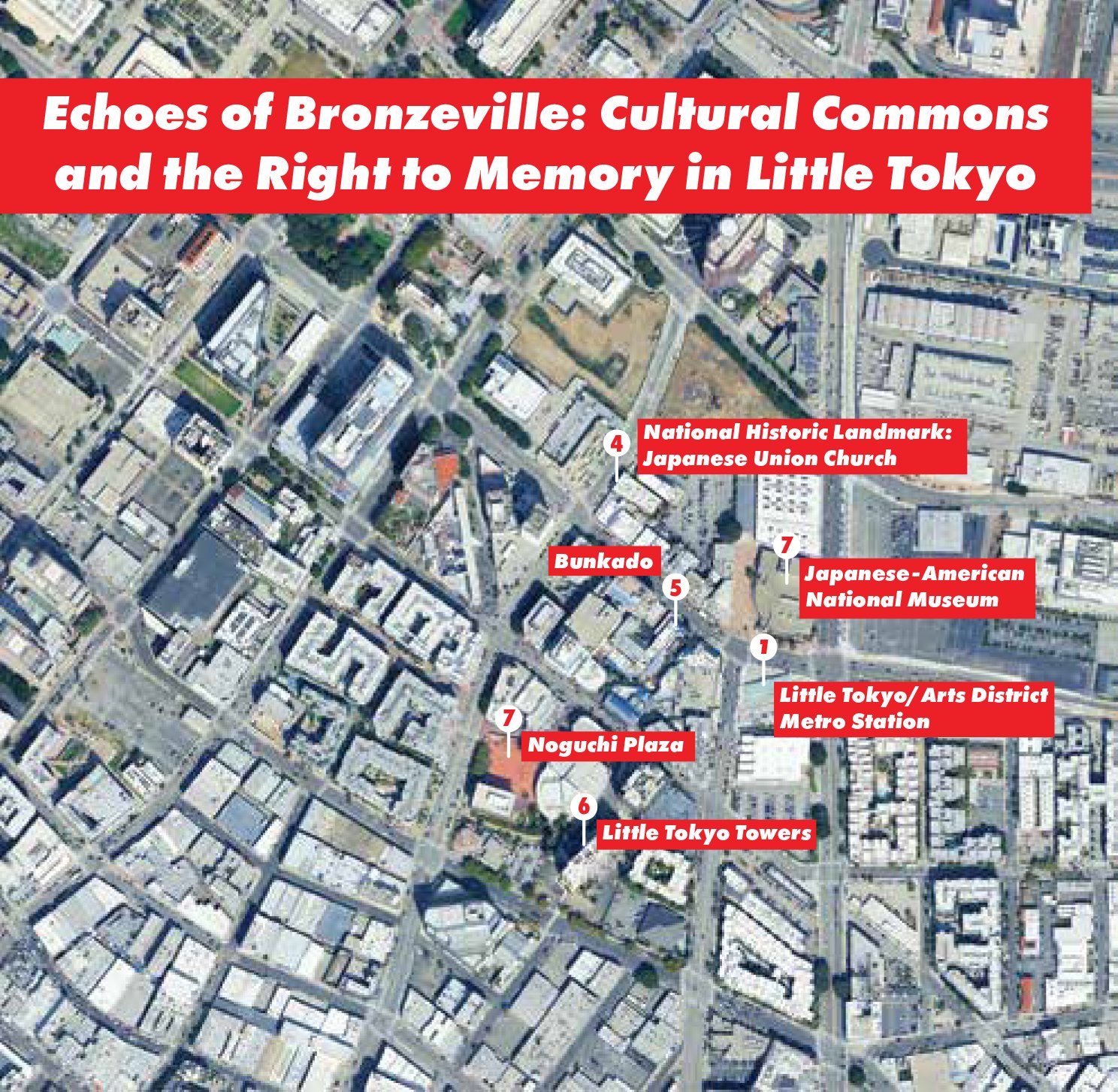

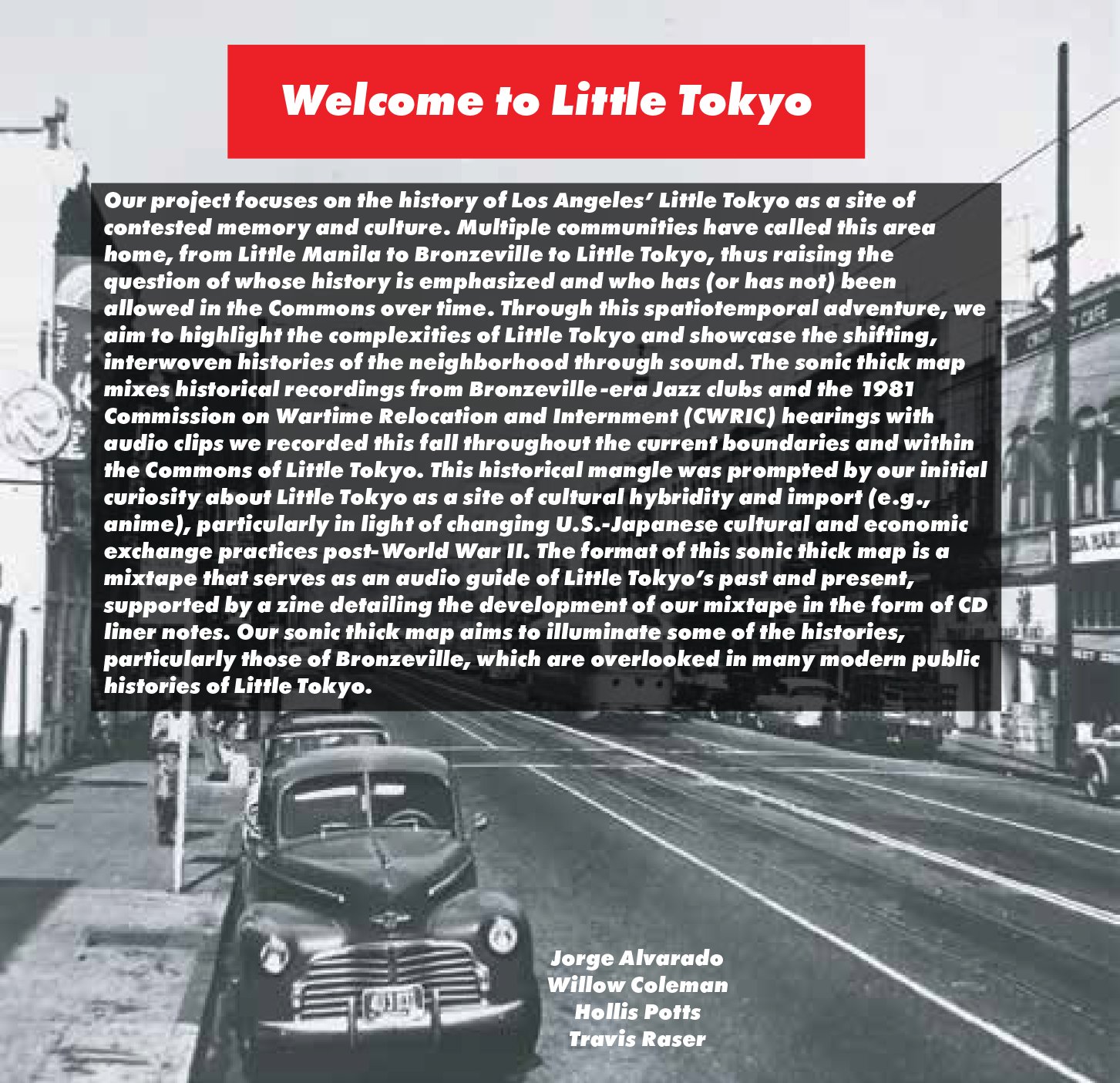

Echoes of Bronzeville: Cultural Commons and Right to Memory in Little Tokyo

Jorge Alvarado, Willow Coleman, Hollis Potts, Travis Raser

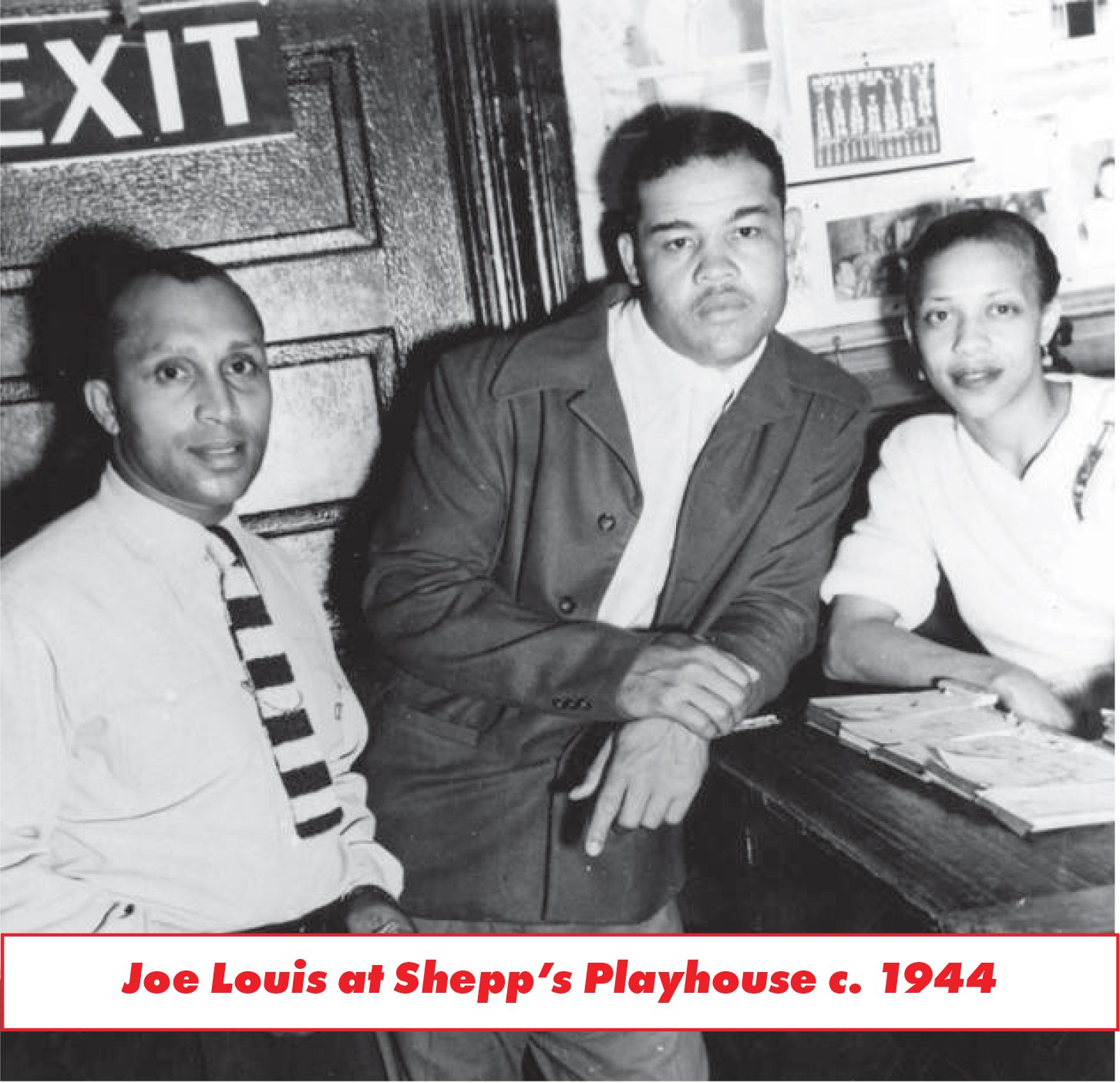

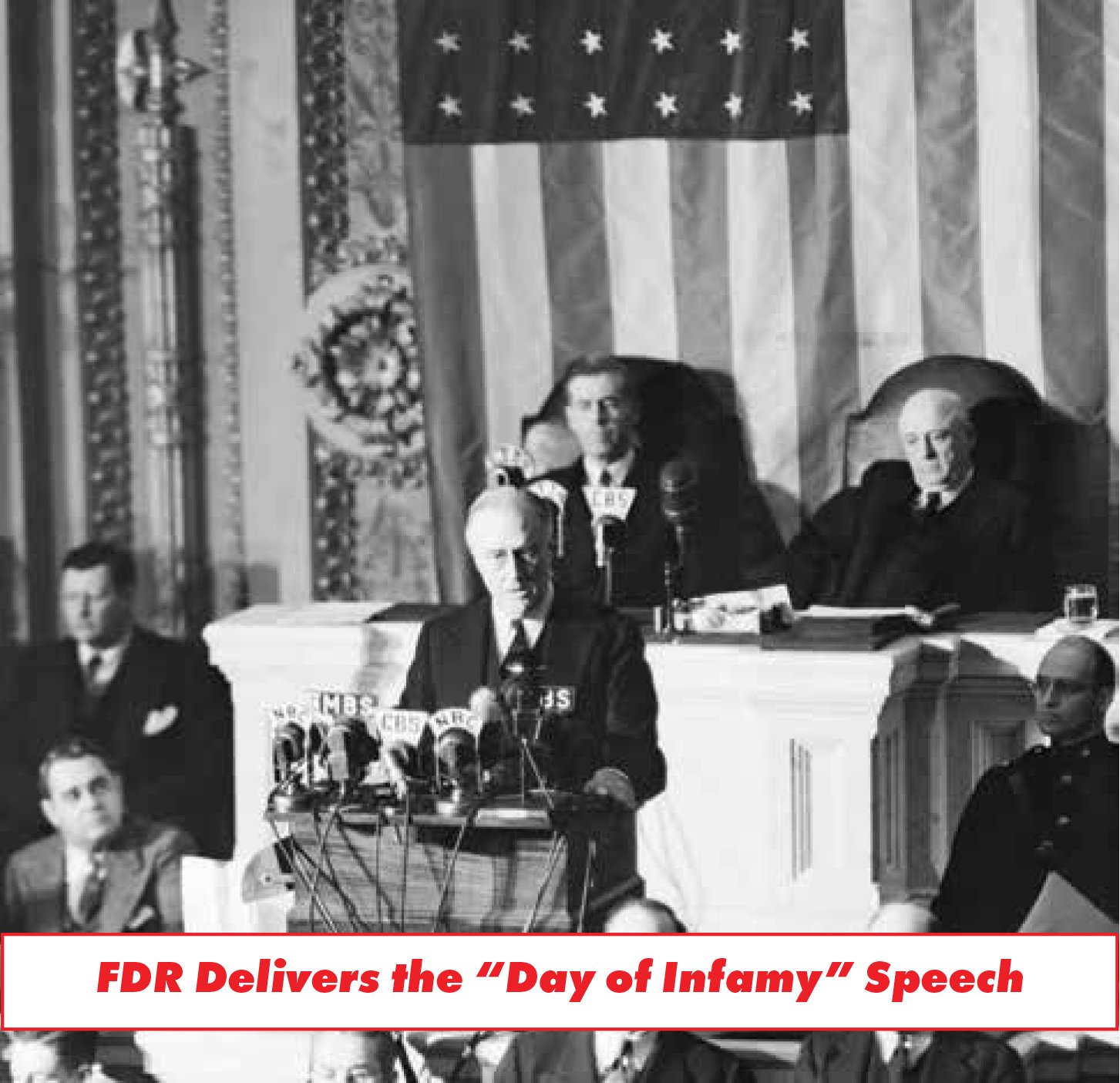

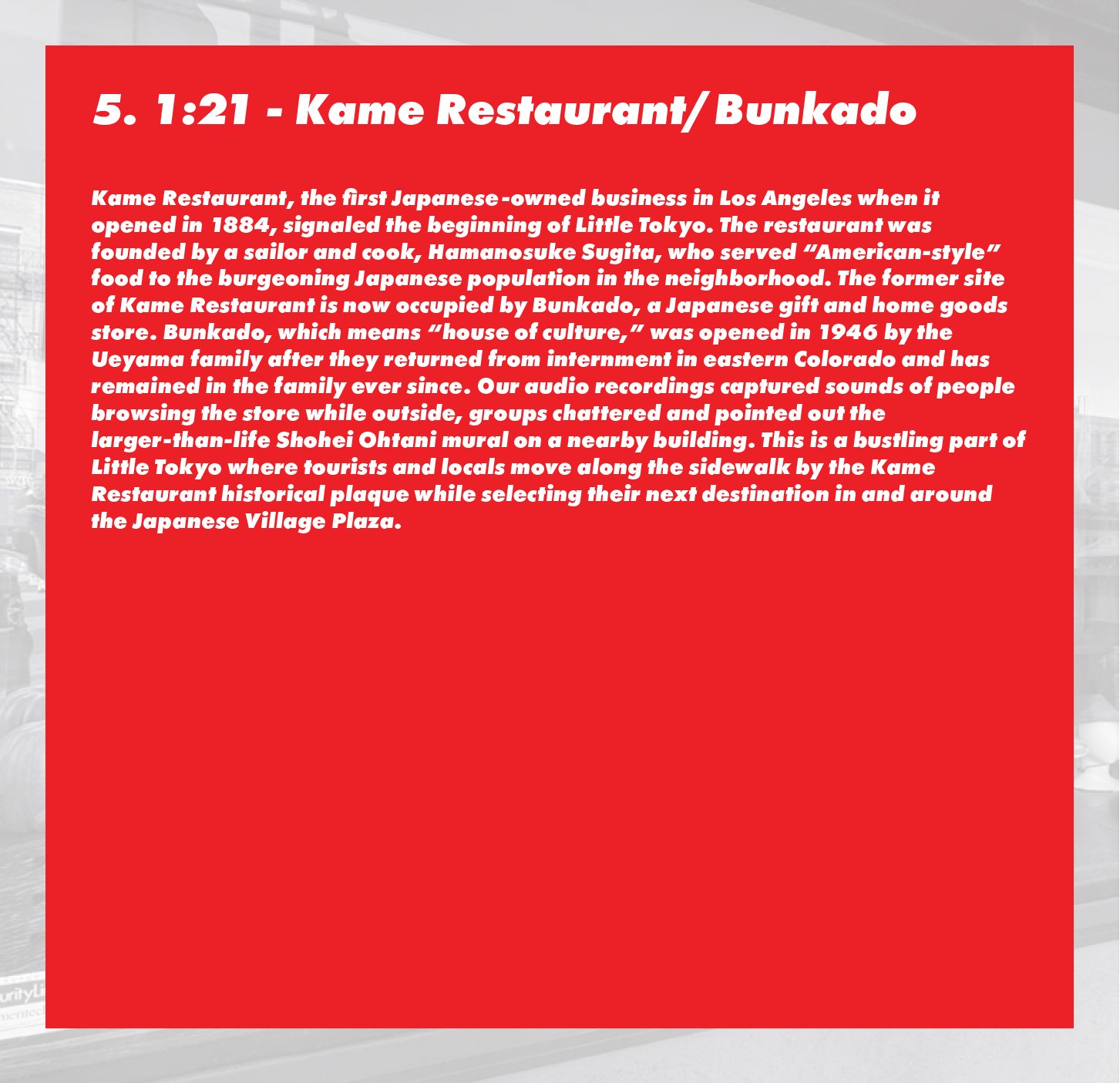

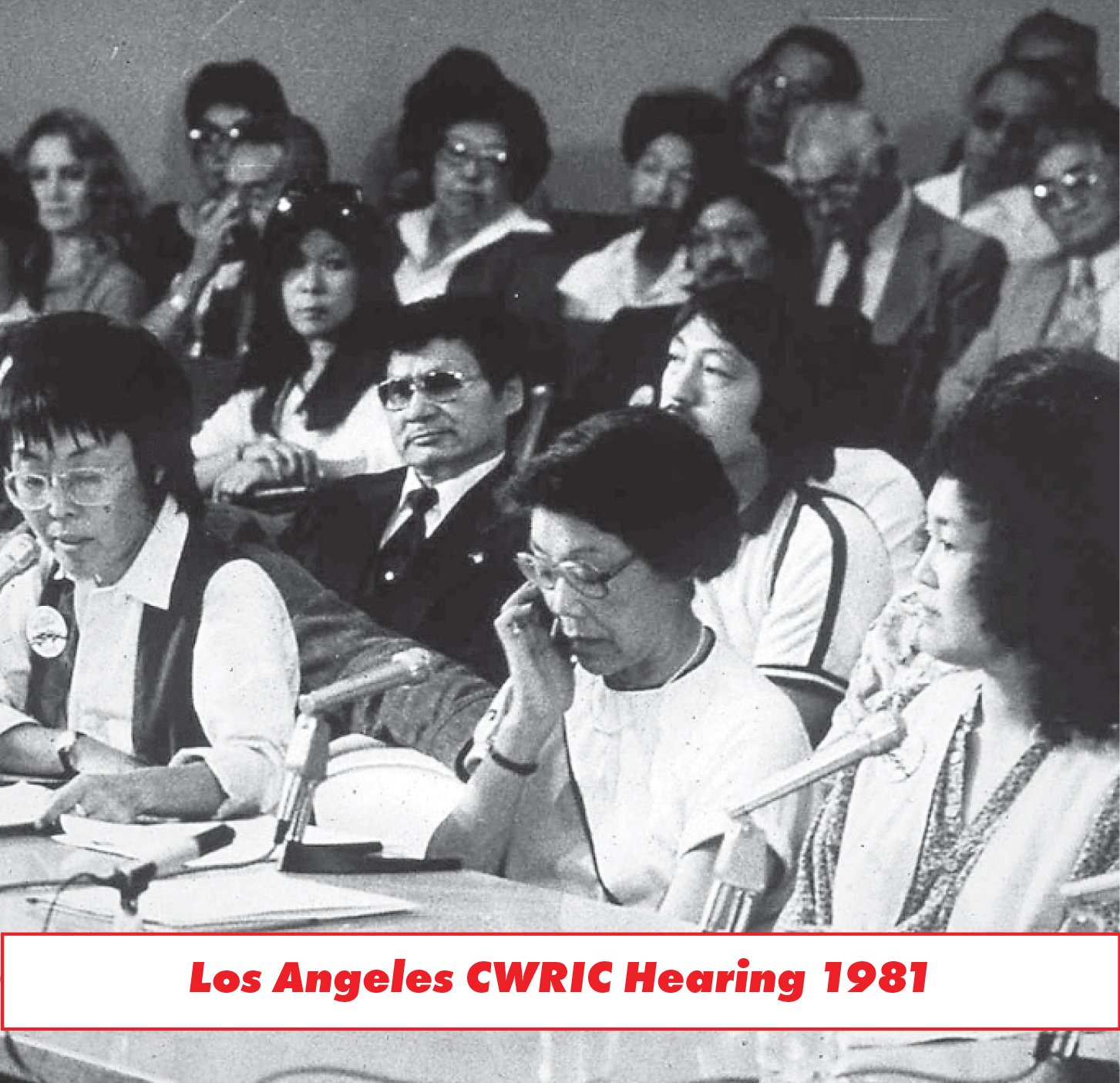

Our project focuses on the history of Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo as a site of contested memory and culture. Multiple communities have called this area home, from Little Manila to Bronzeville to Little Tokyo, thus raising the question of whose history is emphasized and who has (or has not) been allowed in the Commons over time. Through this spatiotemporal adventure, we aim to highlight the complexities of Little Tokyo and showcase the shifting, interwoven histories of the neighborhood through sound. The sonic thick map mixes historical recordings from Bronzeville-era Jazz clubs and the 1981 Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment (CWRIC) hearings with audio clips we recorded this fall throughout the current boundaries and within the Commons of Little Tokyo. This historical mangle was prompted by our initial curiosity about Little Tokyo as a site of cultural hybridity and import (e.g., anime), particularly in light of changing U.S.-Japanese cultural and economic exchange practices post-World War II. The format of this sonic thick map is a mixtape that serves as an audio guide of Little Tokyo’s past and present, supported by a zine detailing the development of our mixtape in the form of CD liner notes. Our sonic thick map aims to illuminate some of the histories, particularly those of Bronzeville, which are overlooked in many modern public histories of Little Tokyo.

Sounding the Divide: Transaction, Song, and Doldrums in the Arts District, Skid Row, and the Spaces In Between

Dusty Frye, Ángela Godoy-Fernández, Cora Johnson-Grau

The neighborhoods of Skid Row and the Arts District hold complex histories; the former with zoning laws, containment policies, deinstitutionalization, policing and disinvestment, as well as advocacy, mutual aid networks, and arts and culture, the latter with manufacturing, factories, warehouses, rail lines, artists’ precarity, developers’ speculation, urban transformation by and through displacement and gentrification. These complexities have often been reduced to singular narratives regarding the spatial and sonic presentation of these neighborhoods. Our thick sonic map traces our path moving from the Arts District to Skid Row, including through the dissonant sonic and physical border in between the two neighborhoods. Our thick sonic map interrogates the relations and disconnects between the two neighborhoods, mapping the spatial inequities between both places sonically. Centering joy in our inquiries, our map also reminds academics of their presence and knowledge production practices.

Beginning in the Arts District, we amplify sounds of surveillance and commerce, reflecting the cycles of gentrification and transaction that drown out its self-identification as a place of art. Moving into the semi-industrial border zone, a "sonic doldrum" emerges as an inhospitable rift that shapes how bodies and sounds can or cannot move between the two neighborhoods. Beginning in the Arts District, we amplify sounds of surveillance and commerce, reflecting the cycles of gentrification and transaction that drown out its self-identification as a place of art. Moving into the semi-industrial border zone, a "sonic doldrum" emerges as an inhospitable rift that shapes how bodies and sounds can or cannot move between the two neighborhoods. In Skid Row, we tune into vibrant sounds of music, art, and resistance, challenging common representations of the neighborhood that are rooted in anti-Blackness and stigmatization of people who are unhoused.

Throughout, we interrogate our embodied positions as students and researchers, inspired by the call from Melissa Acedera, founder and executive director of Polo’s Pantry, to align study with collective liberation. Our audio offers an evolving, imperfect set of sonic directions that recognize the ways that we are oriented in cities are produced by accumulations of injustices and seeks to begin the work of disrupting those injustices by listening and re-orienting.

It’s Called Fashion Alley, Sweaty

Carl de Joya, Emma Spies, Anna Whittell

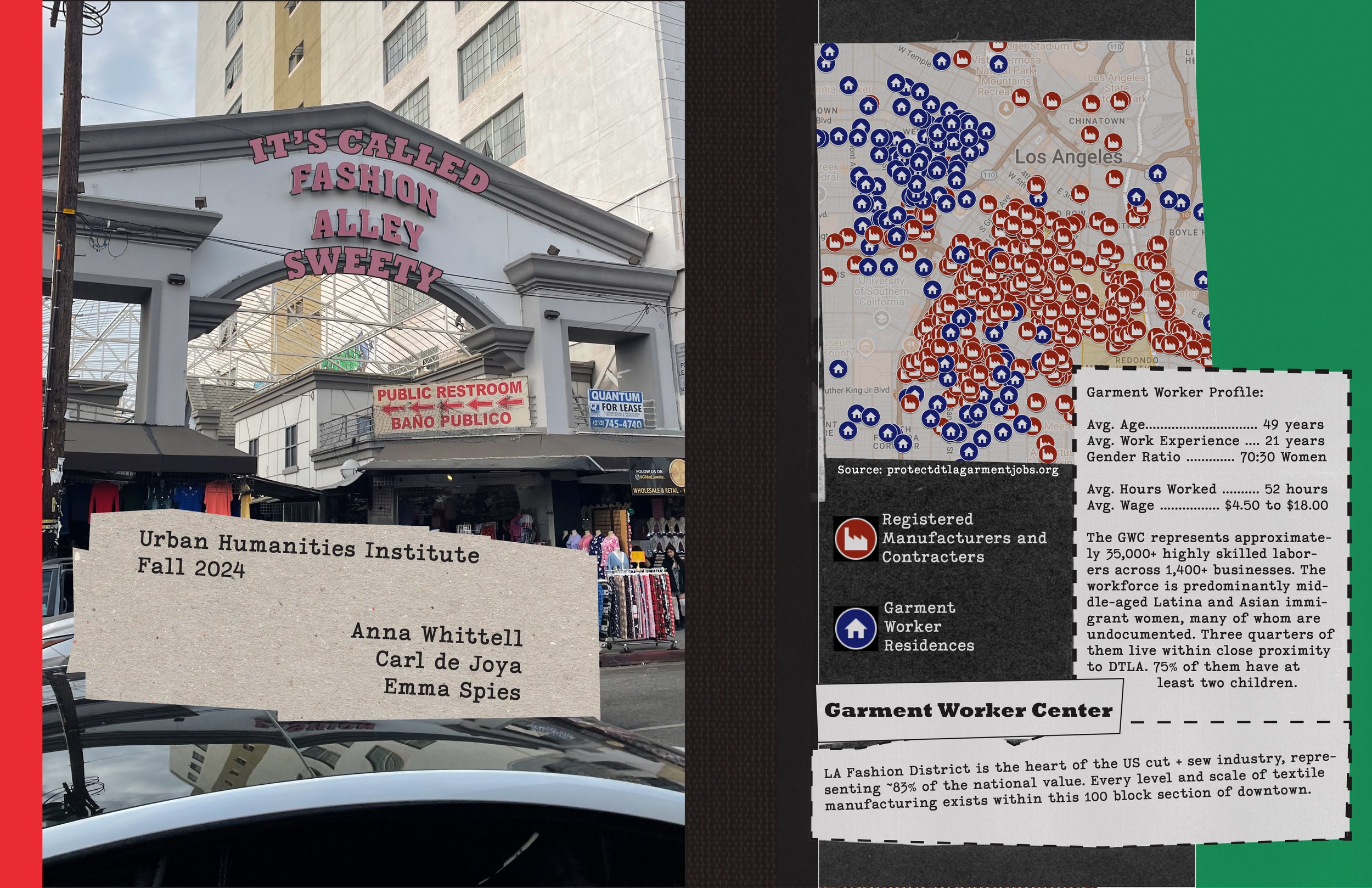

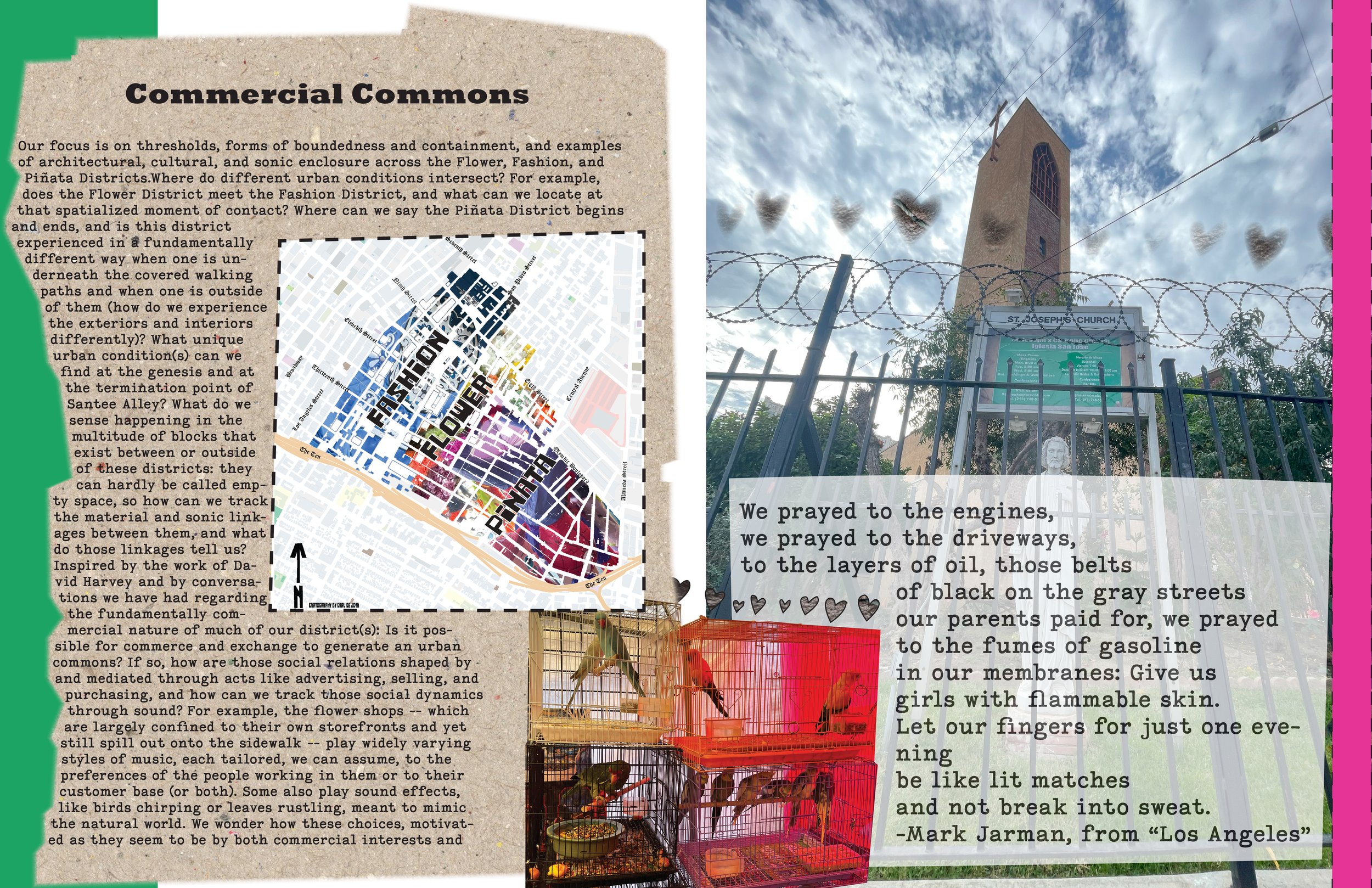

We argue that our district contains a number of distinct but intersecting commercial commons -- groups of people with shared interests engaging in commercial activities specific to their neighborhood and the goods and services it offers -- and that these commons (re)constitute themselves sonically in a way that is unique within Downtown LA. The neighborhoods within our district have historically produced, marketed, and sold different types of goods: the Fashion District sells both garments and wholesale fabrics, the Flower District sells flowers, and the Piñata District sells piñatas, homegoods, and party supplies. Each neighborhood also offers food, drinks, and forms of entertainment unique to the nature of its commons. We argue that a sonic map tracking our movements through our district will demonstrate the ways in which these commercial interactions are simultaneously distinct (bounded off from one another) and intersecting (bleeding into one another). Our thick condition, which features layered sounds of production and exchange, reveals the existence of an auditory economy: this auditory economy both reflects and shapes social relationships throughout our district. Ultimately, this auditory economy reveals how labor intersects with gender, class, and race, as well as the ways in which those intersections articulate how power dynamics within our district unfold across space and time.

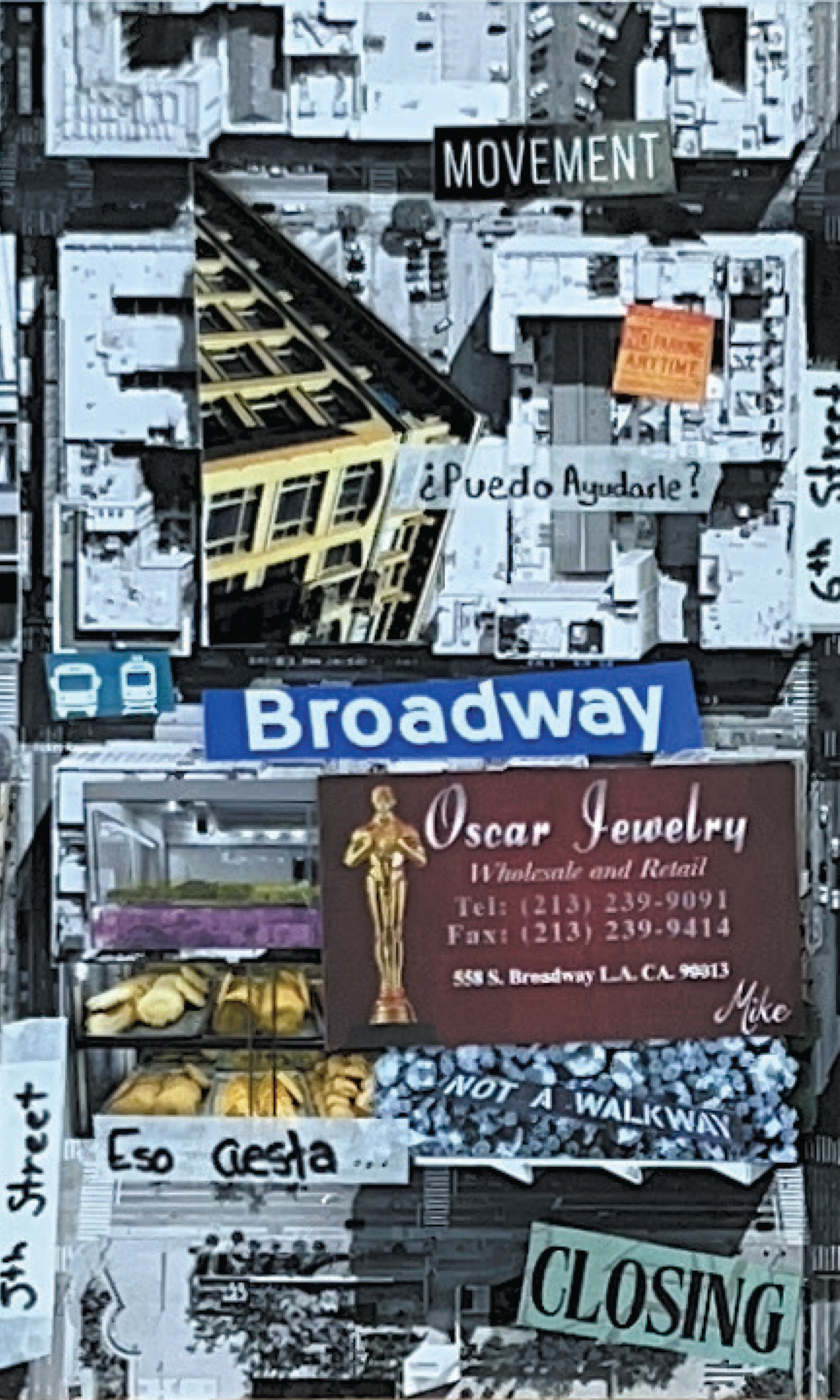

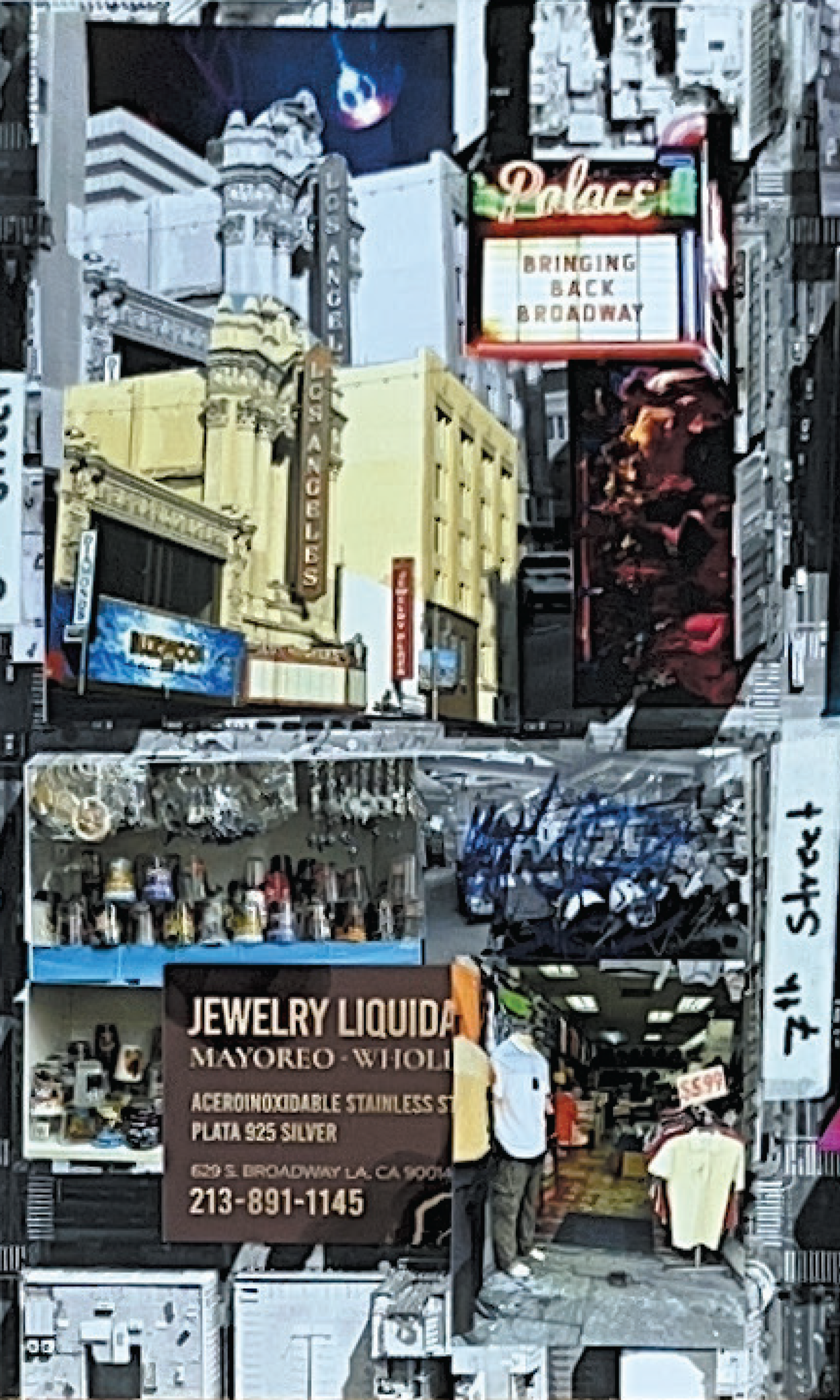

Prosceniums of Broadway

Ana Arreguin Gomez, Remi Messier, Brandt Rentel, Jordan Wynne

Our sonic thick map investigates the threshold between occupancy and vacancy within Downtown Los Angeles’ Broadway Theatre District. As physical configurations shift, Broadway remains a proscenium on which this spatial negotiation occurs. The connotative definition of a “Broadway” suggests a vibrant performance district. In the case of DTLA’s Broadway, many theaters have been adaptively reused to make way for commercial purposes. Formal performative space is thus no longer contained. What sounds, voices, and happenings are audible on the street, and what remains unheard? How are these storied theatres (re)claimed by residents, workers, and patrons? Our project positions Broadway as a proscenium for embodied orientation1 through performance, including our own.

We confine our research between 3rd and 9th streets, to allow for a slight buffer between the central area of commerce. One’s experience of Broadway changes dramatically depending on the time of day. During the daytime, multiple avenues of commerce (jewelry, retail, street vendors) unfold as you approach 7th and Broadway. In contrast, the evening is characterized by a juxtaposition between the cacophonous nightlife and the eerie silence of hollow buildings left for sale. Broadway’s hybrid sonic landscape is punctured with the sounds of lively crowds, artistic performances, storefront conversation, and the constant hum of the streetscape; but more and more, the silent specter of gentrification looms behind the curtain of Broadway’s empty properties. Our sonic thick map sees these acoustic thresholds as doorways into the socioeconomic tensions of Broadway, making audible the conditions by which Broadway’s prosceniums materialize.